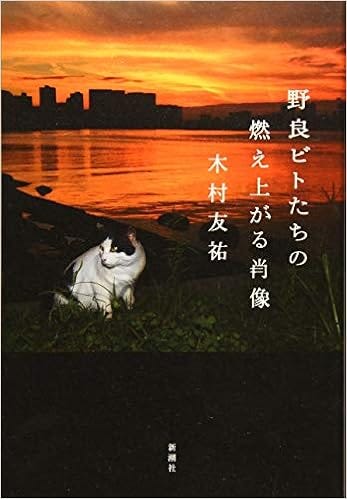

The Homeless Go Up in Flames

「野良ビトたちの燃え上がる肖像」木村友祐、 新潮社、2016

The Homeless Go Up in Flames, Yusuke Kimura, Shinchosha, 2016

I would say that this book is not for the faint of heart, except that maybe avoiding the uncomfortable is a luxury that we shouldn’t resort to so easily these days. There were times I had to put the book down and take a deep breath, and it certainly shouldn’t be read just after eating. Sometimes, to be honest, I didn’t think I could read anymore—the torturing of cats, the body of a dead man so covered by maggots that it seems to be wriggling—but I felt like I would be putting myself squarely with the residents of the gated communities Kimura writes about if I stopped reading.

Source: Storiediavventura

The central character of this novel is 63 year-old Yanagi, a man with over 20 years experience living on the streets. Injured on the job at a construction site, he could no longer work, but has made a dignified life for himself on the banks of a river (Kimura seems to be describing the Tama River). He has a carefully honed routine, collecting cans at night to sell, charging electronic devices using solar panels during the day, and taking walks with his cat Musubi. There are even a few pastoral scenes in the first half of this book as Yanagi sits in a chair in the sun and watches children playing baseball, or a former chef-turned-homeless roasts fish from the river. But disturbing signs in the neighborhood destroy any serenity here. A large gated community goes up, closely guarded. Security cameras and motion-sensor lights are installed in neighborhoods, and signs warn residents not to leave cans out for homeless people to take. Yanagi begins to find cats that have been tortured to death.

An encampment along the Tama River. Source: Storiediavventura

The book was published in 2016 but set in the future of 2018, when Tokyo was gearing up to host the “Tokyo World Sports Festival” in 2020 with “beautification campaigns as well as harsher anti-terrorism measures. The government even enacts a law banning any claims that the economy is less than robust. Belying the government’s claims, more and more people are seeking refuge in the homeless encampment along the river, including types of people that Yanagi had not seen among the homeless before—a young mother and her child, a woman escaping domestic violence, a man taking care of his elderly father, foreign workers, even refugees. Among them is a young reporter, Kinoshita, who had previously visited Yanagi and other homeless to write their stories. When the magazines he had worked for fold and his girlfriend kicks him out, he has to rely on Yanagi’s hospitality.

Vegetable beds cultivated by homeless people along the Tama River (despite signs put up by the government banning such guerrilla gardening). Source: Livedoor

This disparate group of people is increasingly desperate as their usual ways of making a little money are closed off, and run-ins with nearby residents become more common. Fences are put up on the bank, essentially trapping them in, and they lose access to water. But the standoff is not a straightforward conflict between the residents and the homeless people—the homeless blame the foreigners living among them for a terrible fire that breaks out in their encampment. Needless to say, Kimura doesn’t hand out any comfort at the end.

The Tama River after Typhoon Hagibis; Source: Mainichi Shimbun

In the afterword to スクエア (Square), a collection of four dystopian novels, 星野智幸 (Tomoyuki Hoshino) asks why Japanese literature denies and avoids political issues, and calls for “new political novels” that will pursue this question. Hoshino would object to a description of his novels as “dystopian”-- he claims they simply depict reality. And Kimura’s book, unfortunately, does seem to reflect reality, or at least a possible future that we can’t dismiss. Just a few days ago, homeless encampments that once lined the Tama River were swept away by Typhoon Hagibis. Taito ward in Tokyo refused to accept homeless people in its shelter, and a Google search brings up a depressingly long list of cases in which homeless people have been attacked (and yes, even set on fire) and police have done nothing.

On the other hand, protests about Taito ward’s heartless behavior has led to a promise to change the policy requiring anyone seeking shelter to provide an address, and Setagaya ward handed out information about shelters to people living along the Tama River before the typhoon. But it is easy to look past the homeless people we see on the streets, so if nothing else, read this book! And if you can’t read it in Japanese, I can recommend Tokyo Ueno Station, a haunting novel about a homeless man by Yu Miri and translated by Morgan Giles.

A note about the title:

Rather than using one of the more customary words for the homeless, like路上生活者 (literally, “people living on the streets”), 野宿者 (people sleeping outdoors) or ホームレス (“homeless” written in katakana), the residents living around the homeless encampments in this book coin a new word that dehumanizes the homeless by using the same term, 野良, that is used for stray or feral cats and dogs. “Person” is not even written in kanji or hiragana (人 orひと)—by using katakana here (ビト), they are further isolated from the human community. My very rough translation of the title doesn’t even begin to get at everything Kimura was trying to convey.