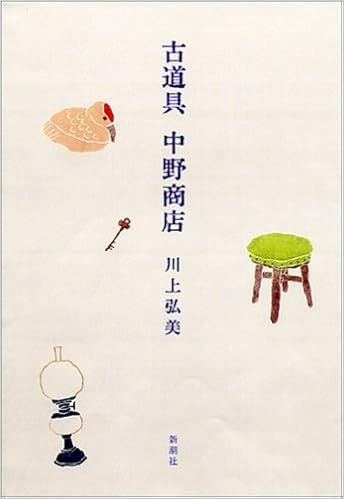

Nakano’s Secondhand Store

古道具 中野商店

川上弘美

新潮社, 2005

Nakano’s Secondhand Store

Hiromi Kawakami

Shinchosha, 2005

*Since this post was written, the English translation has been published as The Nakano Thrift Shop, translated by Allison Markin Powell .

If I was looking for the antithesis of the glossy j-dramas* I love to watch, I think I’ve found it in 古道具 中野商店 (Nakano’s Secondhand Store) by 川上弘美 (Hiromi Kawakami). Nothing is wrapped up neatly with a bow by the end of the book, there is no penultimate scene in which the characters realize how they “truly” feel, and there are no episodes of recrimination and reconciliation. I am not giving anything away here because I don’t think anyone reads Kawakami’s novels for plot twists and reveals, but rather for the mood she creates from the first page to the last.

Haruo Nakano opened his secondhand goods store about 25 years ago on the outskirts of Tokyo when he got tired of life as a salaryman. He always stresses that this is not an antique store, and Kawakami’s descriptions should quickly erase any pre-formed image of a charming store full of treasures the reader may have had.

This is the set for "Biblia Koshodo no Jiken Techo," a j-drama set in a bookstore, and provides the perfect example of what Nakano's Secondhand Store does NOT look like (and you can never have too many pictures of bookstores).

This is closer to my idea of what Nakano's shop looked like.

Nakano’s store is crammed full of everything that would have been standard in a house from the middle of the Showa era (1926-1989)—low tables, old fans, air conditioners, pottery and kotatsu. Every day, Nakano would open the shutters in front of his store, cigarette dangling from his mouth, and arrange items that he thinks will bring customers in—old-fashioned typewriters, the prettier crockery, lamps with a little artistic flair, and paperweights in the shapes of turtles and rabbits. As he works, ash falls from the tip of his cigarette onto his stock, but Nakano just brushes it off with the edge of his apron. Reflecting his slapdash style, his "Open" sign is just a scrap of cardboard with a few characters scrawled in black marker on it.

A secondhand store in Tottori prefecture

Nakano runs the store with the help of Hitomi, our narrator, and Takeo. As Hitomi is telling the story, we hear her observations about everyone around her, but get few details about Hitomi herself, leaving the reader to guess from context that she is in her early 20s and drifting a bit in this dead-end job. Takeo, who is in charge of replenishing the store’s stock, is another lost soul. He was bullied in school and stopped going entirely after he lost half a finger when his tormentor slammed it in a door. His loss of faith in people prevents him from leaving his shell much, but he is gentle and kind when he can spare the energy.

Masayo, Nakano’s sister, stops by nearly every day, and her charisma always boosts sales. In her mid-50s and with an independent income that enables her to style herself as an artist, Masayo holds exhibitions of the rather creepy dolls she makes, or cloth she has dyed shades of brown using leaves. Although they are past middle age, Masayo and her brother are more free-spirited than Hitomi and Takeo, who seem buttoned-up and scared of life in comparison. Ironically, Masayo and Nakano, who is on his third wife and also has a mistress, come to inexperienced Hitomi for advice and commiseration. Nakano even asks Hitomi to read the erotic novel his mistress has written and give her opinion.

Each chapter has a title like “Paperweight,” “Celluloid,” “Sewing Machine” and “Punching Ball,” and it becomes a bit of a game to spot each of these objects in the chapter as you read. Sometimes they are tangential to the story, sometimes they play a central role. The chapters were initially serialized in the literary magazine 新潮 (New Tide) from 2000 to 2005, and are each centered on a different episode, often involving the store’s unusual clients. “Paper Knife” is about a deranged woman who “stabs” Nakano with a paper knife. “Big Dog” relates Takeo and Nakano’s visit to a yakuza to buy a helmet and armor in a deal that they seal with whiskey and chocolate cake. “Bowl” is about a man who brings in a beautiful bowl that he believes his ex-girlfriend has cursed, bringing him a wave of bad luck. In “Paperweight,” Nakano sends Hitomi to check up on Masayo after an elderly relative reports that she is living with a man.

The thread running through all of these chapters is Hitomi’s yearning for some kind of relationship with Takeo. She’s not always sure what she wants from him, and yet she feels attached to him by a thread that draws taut when he’s nearby and snaps when he leaves. They tentatively reach out to each other, but after several awkward dates and even more awkward sex, Takeo apologizes to Hitomi, admitting that he’s just not that interested in sex. Later, he tries explaining again:

“Hitomi, I’m sorry that I'm not good at this,” Takeo said quietly.

“That’s not true! I’m not good at this either.” “Really? So…”

For once, Takeo looked me straight in the eye as he spoke.

“So you’re not any good at this whole living thing either?”

Takeo took a cigarette from the crumpled package Nakano kept in the back of the shelf and lit it.

I took one too and tried taking a puff. Takeo spat into a tissue just like Nakano always did. Instead of answering Takeo’s question, I asked when he thought Nakano would come back.

Takeo said, “Who knows.” Then he pursed his lips and breathed in the tobacco smoke. This passage is a good example of the way in which Hitomi and Takeo—and indeed, all the characters here to some extent—keep their distance, even as they make tentative forays toward each other. And Kawakami preserves a distance between the reader and her characters—even though Hitomi is our narrator, we do not know any more about what she is thinking than Takeo does.

But I don’t mean to suggest that this book leaves the reader out in the cold. Hitomi’s decision to forget Takeo and “eat vegetables and seaweed and beans and be healthy and sparkling every day” made me laugh even as I sympathized. Kawakami is particularly good at juxtaposing comedy and poignancy in this way so that you don’t know whether to laugh or cry. In “One Piece,” Hitomi is fretting because Takeo isn’t answering her phone calls. Going right to extremes as usual, Masayo suggests that maybe he has died, but Hitomi thinks it much more likely that when she called, Takeo was eating a cream-filled pastry and his fingers were so greasy he couldn’t press the right button. Or his phone is in his back pocket but he’s gained so much weight that his jeans are too tight and he can’t pull the phone out of his pocket. Or he’s rescued an old lady who fell and is taking her to the hospital.

And then there’s Masayo, eating pie and cream puffs in her garish hand-printed scarves as she asks Hitomi how she can keep Maruyama, her boyfriend, interested when her libido is waning with age. One moment Kawakami is painting a picture that almost seems to encourage us to look down on Masayo, and then the next moment she upends our comfortable assumptions as she describes Masayo confessing to Hiromi that she loves Maruyama best in all the world. Hitomi is struck to the core as she realizes there is no one about whom she can say the same thing. Although Hitomi and Takeo frequently shake their heads at Nakano and Masayo’s irresponsibility and impetuousness, at least they seem to have gotten something from their gambles.

The final chapter is set about three years after the events of the previous chapter. Hitomi wakes up confused, thinking she is back in her old apartment by Nakano’s store, even though she moved two years ago. The relatively short time she spent working there was so intense and luminous that she is still partly reliving those days. And don’t we all have periods like this, bookended by the less vivid days that came before and after?

Although Kawakami’s writing style always keeps the reader at a modest distance, she lets the reader stand just outside Nakano’s store, peering through the window, as it were, at her four characters. In the hands of such a skilled author, this does not feel alienating. Standing alongside Kawakami, we keep a respectful distance and sigh with exasperation when Nakano is enticed by yet another woman, blush for Hitomi’s awkward attempts to approach Takeo, squirm in embarrassment when Masayo gives Hitomi inappropriate advice, and fear for Takeo. And just like Hitomi, the world seems a little greyer when we leave their company.

You can read more about Hiromi Kawakami here. She has won numerous literary prizes, and at least two of her novels are available in English translation: 先生の鞄 (The Briefcase) and 真鶴 (Manazuru). The Briefcase would be a good entry point. This tender novel is about a woman and her relationship with her former teacher as it shifts from friendship to love, with food and the changing seasons as a running theme.

* If you didn’t immediately know that “j-drama” refers to the wonderful world of Japanese dramas, then you’re missing out. I’m sure many people—with more refined taste than myself, no doubt—would disagree about that, but they’re worth a try if you’ve never seen one. All of the major TV channels broadcast these dramas consisting of 10-12 episodes, with a new line-up starting in the fall, winter, spring and summer. The storylines cover a huge range, with everything from crime and high school angst to period dramas and the search for a husband. Try ホタルノヒカリ (Hotaru no Hikari) seasons one and two for a mix of comedy, romance and office life. This past season’s 家族の形 (Kazoku no Katachi) is a genuinely good family drama with excellent acting (with English subtitles here and with Japanese subtitles only here). And for a decidedly non-glossy j-drama with a slow pace, お菓子の家 (Okashi no Ie) is a bittersweet drama with fine acting from Joe Odagiri (with English subtitles here and with Japanese subtitles only here).