Misumi Kubo's Trinity

トリニティ、窪美澄、新潮社、2019 (Trinity, by Misumi Kubo, published by Shinchosha in 2019)

In an essay entitled「五十歳の私」 (“Myself at 50;” published in 2016), Misumi Kubo writes that she was surprised when her first book was published at age 44, but is equally surprised to find herself alone at age 50. She took her child and left her husband when her child was 15, and having successfully steered this child through school and finalized her divorce in 2014, she is now truly on her own. Perhaps this sense that one part of her life has been completed, and with it the tug-of-war between family demands and her own work, inspired Kubo to write this novel, which illustrates the struggle between the desire for work, love, children and marriage through the lives of three women—Suzuko, Taeko and Tokiko. As the title “trinity” suggests, the characters discover that you can only have three of these at best, and might lose all of them in the fight to hold on to one ambition.

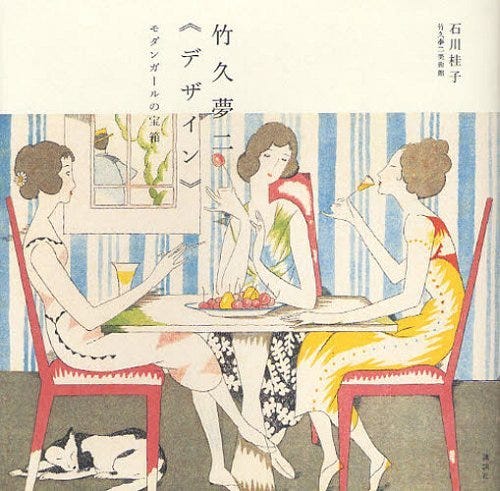

Source: 竹久夢二《デザイン》 モダンガールの宝箱, 石川桂子/著

The novel begins in the present day, when Suzuko gets a phone call telling her that Taeko had died. Suzuko attends the funeral with her granddaughter Naho, an aspiring writer who has always been intrigued with Suzuko’s brief career at a famous magazine. Naho was only able to find a job at a “black” publishing company, known for working its employees into the ground. Having suffered a nervous breakdown due to overwork, even leaving the house for this funeral is a major step for Naho. After Suzuko introduces Naho to Tokiko at the funeral, Naho begins visiting Tokiko every week to hear the story of these three women and their careers at the magazine.

Source: Official Olympic Book

Suzuko, Taeko and Tokiko meet in 1964, the year of the Tokyo Olympics. They had grown up when disabled war veterans were a common sight on street corners, but now these relics of the past are being swept away by a wave of new consumer goods and the sense that Japan is heading confidently into the future. The three women all feel that their work at a cutting-edge magazine is in some way creating this new atmosphere in Tokyo.

Taeko, the magazine’s chief illustrator, was born to an unwed mother and then farmed out to a childless woman in the same town, until her mother was able to save enough to bring her to live with her in Tokyo. After art school, she trudged around Tokyo with her portfolio until someone recognized her talent. Of the three woman, Taeko is the one who makes a name for herself as an artist, and yet she finds that her attempt to have it all—love, marriage, a child and work—leaves her, in the end, bereft of all four.

Source: Akihisa Sawada

Tokiko works as a freelance writer for the same magazine. Her mother and grandmother had also been freelance writers who had supported their families singlehandedly with this work, and Tokiko grew up in relative luxury. She is a straight-talking, intimidating woman with her own unique fashion sense who can write fluently on command, but ultimately gets fed up as she realizes that even the supposedly cutting-edge magazine she works for always runs stories about male politicians, male artists, and male authors, nearly all written and edited by men, and always with nude pictures of women inserted in the middle.

Source: Junichi Nakahara

In contrast to Tokiko and Taeko, Suzuko poured tea and did odd jobs at the magazine, and only worked there a few years before she married. Suzuko understood that for women to live lives of freedom, they needed impressive talents, like Tokiko and Taeko had, that could be translated into money. She had no such talents, but she had seen how hard her mother had to work in the family shop selling 佃煮(food boiled in soy sauce), and had grown up with the smell of concentrated soy sauce and the stench of the drainage channel running by her house. Suzuko craved stability, which she felt she could get by marrying a salaryman and living in one of the new apartment blocks.

The night when the three women go together to the demonstrations in Shinjuku commemorating International Anti-War Day, on October 21, 1968, seems to be the high point of their lives. At the demo, the students around them yell anti-war slogans, but Suzuko, Taeko and Tokiko scream out their own frustrations (Kobo, born in 1965, said in an interview that she remembers these demos very clearly, and recalls thinking that surely not all of the protestors were protesting the Vietnam War. She was particularly interested in what the women were thinking, and this section of the book seems to be her attempt to answers= that question.) Suzuko encourages Taeko and Tokiko to draw the girls at the demo and get their stories, leading to a night of frenzied but inspired work as they dodge the police.

Infuriatingly, the three are scolded by their male bosses for having taken the unconscionable risk of joining the demonstrations, particularly as their prize illustrator could have been injured (and thus rob the magazine of her unique pictures of men and boys that gave the magazine its style). This seemed like a harbinger of the forces, both historical and personal, that began to pressure these women.

History is always present in the margins of this book, sometimes benign (the glossy white washing machines and vacuum cleaners promising to make women’s lives a little easier), sometimes threatening. As Suzuko suffers through her first pregnancy, she watches Yukio Mishima on TV talking about his Tatenokai (Shield Society), a private militia he had founded. A few years later, as she pastes family photos into albums, she watches, astounded, as Mishima commits suicide on TV. Kubo seems to include these historical details into the larger storyline as a reminder that, while our lives may be temporarily subsumed by our personal concerns, history is always happening around us.

These historical forces don’t remain confined to the margins for long. Tokiko senses a major historical shift in 1995, the year that began with the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, followed by the Tokyo subway sarin gas attack in March. The small company that had published her essays collapsed, and gradually the magazines she had written for folded. After nursing her husband through a long illness, she was left with nothing but her pension. The sense of limitless possibility was gone by the time Naho was born. Reading this made me feel like history had let these women down. Although women have made progress in so many ways, in other ways things don’t seem so promising in the present day, as highlighted by Naho’s problems finding a job at anything other than a black company and Tokiko’s penury in old age.

Reading Misumi Kubo’s books feels like a full contact sport. 「ふがいない僕は空を見た」 (The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky) left me physically exhausted but also completely exhilarated. She hits you in the gut, makes your heart hurt, and yet makes you feel more alive, all at the same time. Trinity is more of a slow burn than her other books, which just shows the extent of her range.

Unfortunately, none of Kubo’s novels have been translated into English yet, but Polly Barton has translated “Mikumari,” the first section of The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky, as a stand-alone short story, published by Strangers Press.