Immersion with Strangers Press

I have been reluctant to write about Japanese literature already translated into English because there are plenty of others spreading the word and I want to focus on books that have not received much attention outside of Japan. However, unless the translated works that do get out there find readers, we can hardly expect publishers to give us more Japanese works in translation. And since I haven’t heard much about the Keshiki series published by Strangers Press, I thought it was worth a mention here (I heard about it on my one-and-only visit to Twitter, which just goes to show you can find treasure among the garbage).

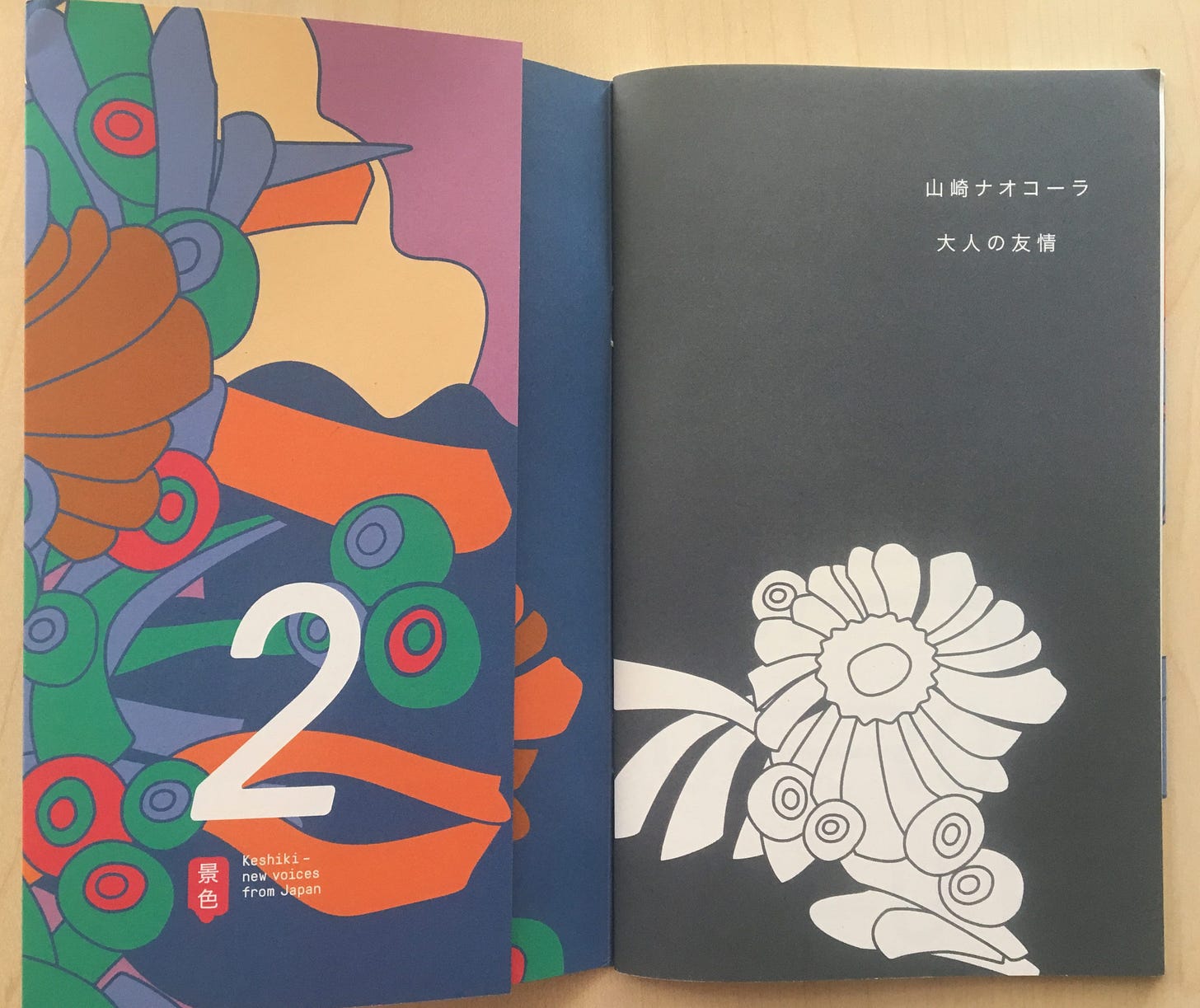

Strangers Press publishes translations in collaboration with the British Centre for Literary Translation, the University of East Anglia and Writers’ Centre Norwich. Keshiki, a set of eight short stories, is their first project. First of all, I have to say that these eight chap books are things of beauty. They have French flaps and are lovely to hold, reminding me of everything I love about Japanese book design, particularly bunkobon, the small paperback editions that fit so well in the hand. Each story has its own unique cover design, and introductions by well-known writers such as Pico Iyer, Karen Russell and Naomi Alderman.

All eight of the stories have distinct plots of their own, but there are some common threads running through them. There is a sense of dislocation in all of them, which prevents the reader from getting entirely comfortable, but also makes us sit up and read more closely. In Yoko Tawada’s “Time Differences,” Michael, Mamoru and Manfred are all in different time zones, living outside of their home countries and all yearning for a different man. The dislocation is more gentle in Nao-cola Yamazaki’s “The Untouchable Apartment” (one of the three stories in “Friendship for Grownups”), in which a young woman goes with her ex-boyfriend to see the vacant lot on which their apartment had once stood, but it reaches an extreme in “Spring Sleepers.” Here, Kyoko Yoshida describes a man’s descent into such severe insomnia that he loses his memory—and the reader loses all grasp of reality along with him. In “The Transparent Labyrinth,” Keiichiro Hirano describes the horrific experiences, straight out of a Gothic novel, of a Japanese businessman traveling in Hungary and a Japanese woman he meets there. He spends years trying to find equilibrium again. In “The Girl Who is Getting Married,” by Aoko Matsuda, both the narrator and “the girl who is getting married” seemed to be entirely fluid constructs, leaving me feeling wrong-footed but intrigued enough to read it three times.

Many of these characters do not seem quite comfortable in their own skins. In “Mariko/Mariquita,” Natsuki Ikezawa writes of a Japanese man who visits Guam to study an island religion and feels no affinity to the Japanese tourists at his hotel (“pale, diet-slim, big-headed Japanese couples and package tourists, every one giving off an out-of-place smell”). And yet he cannot quite bridge the gap with Mariko, a Japanese woman he meets who blends in so well that the locals call her Maria or Mariquita.

This search for a place to belong, whether found in a person or a physical location, is another theme I found here, most obviously in “Mariko/Mariquita,” but also in “At the Edge of the Wood.” In this mix of fairy tale and horror story, Masatsugu Ono writes of a father trying to make a home for his son at the edge of the woods. These woods seem to be alive, with “roots tangled in fatigue and loneliness” and trees which “pat each other familiarly on the shoulders and back and sometimes wriggle their hips as they hurry on ahead.” In Nao-cola Yamazaki’s short story “Lose Your Private Life,” Terumi is looking for love—or maybe just a plot for one of her novels.

Misumi Kubo’s “Mikumari,” tells of a high school boy who is having an affair with Anzu, a cosplayer he met at a comic market. This story was the one I was the least excited to read (it won the R-18 prize for erotic fiction, not usually my favorite genre), but it ended up being my absolute favorite of the eight because it somehow managed to be charming, poignant and funny all at the same time. Instead of making me squirm, the sex scenes made me laugh—the boy has to put on a costume, complete with purple wig, before he can have sex with Anzu (also in full costume), and then he goes home and helps his mother with her midwifery practice! Thanks to this introduction to Misumi Kubo, I now have several of her books, including 「ふがいない僕は空を見た」, a series of five linked stories that include “Mikumari.”

That is the best part of this series—it introduced me to new favorites, opened my eyes again to the sheer breadth of Japanese literature, and took me out of my comfort zone (which is a good thing every now and then). Some of the stories were more traditional in structure than others, and one I frankly wanted to throw against the wall because I couldn’t understand what was going on, but they were all provocative and absorbing. I highly recommend reading the entire set.