Food Nostalgia

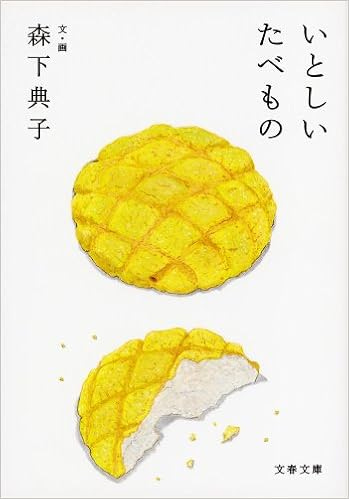

「いとしい食べ物」森下典子

文藝春秋, 2014

My Darling Food, Noriko Morishita

Bungeishunju, 2014

[No English translation available]

In the introduction to「いとしい食べ物」, Morishita notes that “The taste of food always comes with the spice of memories.” Blowing on a hot bowl of ramen calls up memories of Tajima, a college student who lodged with her family when she was young. He had a very particular method for eating ramen that entranced Morishita: he'd carefully pick up noodles with his chopsticks, and then raise and lower them several times before slurping them up enthusiastically.

Tajima returns to Hokkaido to take over his family’s ryokan (traditional inn), but life does not go smoothly for him. After a few new year’s cards announcing his marriage and the birth of children, they hear no more from him until one of Tajima’s friends tells them that his family had declared bankruptcy and Tajima was now divorced.

Tajima comes to visit many years later, and Morishita’s mother makes ramen to mark the occasion. Watching him lift and lower the noodles before inhaling them, Morishita notices that he’s crying unreservedly. Morishita’s parents pretend they don’t notice, and Morishita, feeling that she’s seen something forbidden, slurps up her noodles exaggeratedly, as if to cover for him.

The 22 foods Morishita describes in corresponding essays all carry similarly vivid memories for her. She uses food to position her generation, describing オムライス (omelet over ketchup-flavored rice) as the defining food for children who grew up from about 1955-1975. Bulldog sauce and Kagome ketchup were on every table, and she couldn’t possibly consider eating tonkatsu (breaded and fried pork) or オムライスwithout them.

オムライス (omelette rice); picture drawn by Noriko Morishita

Tonkatsu; picture drawn by Noriko Morishita

Curry was also gaining popularity around this time. As a little girl, Morishita eats dinner at a friend’s house and is amazed to find that they put chunks of beef in their curry, while her family’s curry was full of vegetables and a few thin slices of pork. This taught her that the ingredients families used in their curry revealed their economic station.

Curry and rice; picture drawn by Noriko Morishita

Morishita’s love of food is so all-consuming that she makes associations between food and movies and books that surely wouldn’t have occurred to anyone else. In one essay, she compares the dangerously enticing sex appeal of Antonio Banderas to くさや (kusaya), a kind of fermented fish from the Izu Islands that some people find irresistible, despite its overwhelming smell.

Kasuya; picture drawn by Noriko Morishita

Eating 水羊羹 (mizu yokan, a soft sweet bean jelly) reminds her of the geisha Komako from Yasunari Kawabata’s Snow Country. Both mizu yokan and Komako are fresh, cool, and cling tightly (the mizu yokan to its case, and Komako to her lover), and once their resistance has been broken down, their seductiveness overwhelms the senses. And I’m sure there’s no precedent for her comparison of eggplant to the movies of Yasujiro Ozu, but for her, both of these were an acquired taste she didn’t gain until she was much older.

Although she loves the traditional Japanese sweets made with the same methods and equipment for generations, Morishita is no food snob. Two of her essays are about instant noodles. Sapporo Ramen helped her get over her first breakup and an argument with her boyfriend over whether Donbe Udon tasted artificial led her to realize he wasn’t right for her.

Morishita writes with a wry sense of humor that, as often as not, she uses to skewer herself. She apparently feels no embarrassment in describing her childhood gluttony in an episode during which she ate so much Castella (a cross between pound cake and sponge cake that was originally brought from Portugal) that she made herself sick. Her love of food even spreads beyond mealtimes. After her grandmother gives Morishita her first taste of salted fish, she dreams of the taste and the crackling skin to the point that she sees its shape in a map of South America at school and can’t take her eyes off of it.

Salted and grilled salmon; picture drawn by Noriko Morishita

Map of South America resembling salted salmon; picture drawn by Noriko Morishita

In one of my favorite essays, Morishita writes about Ochugen and Oseibo, a custom of giving gifts to people that you are indebted to in some way in July and December, respectively. Although her mother always insisted they were poor, during these two seasons of the year Morishita always wondered if they were rich after all. At this time, they lived in a one-floor house with a single room about the size of six tatami mats that they used as bedroom, living room and dining room.

Gifts for Oseibo and Ochugen; picture drawn by Noriko Morishita

Her father worked in the material procurement department of a shipbuilding company, and during a few weeks in July and December, the flood of gifts delivered by department stores threatened to overflow their house. These were generally gifts of canned fruit, Pelican soap, vegetable oil, Twinings tea, and Suntory whiskey that they would share with neighbors once deliveries reached such a frenzied pace that the boxes blocked the windows. She describes this period perfectly:

The world was so full of vigor that even a child from a salaryman’s household, growing up jammed into a single six-tatami mat room, could mistakenly assume that her family was rich. None of us doubted the saying that "tomorrow would be more prosperous than today." We all looked upward, just like airplanes taking off into the sky. At that time, companies were growing fast, and salaries and bonuses were climbing straight up.

One day, a basket of matsutake mushrooms are delivered, a gift from a steel company. Still covered with dirt from the mountains in Tanba, they had been picked that morning and then flown to Tokyo on a JAL plane. Morishita’s father declares that these will not be shared with their neighbors. That was the last time that she ever ate matsutake from Tanba. When she was an adult, she ate matsutake several times, but they were never anything like the matsutake that she remembered from that day in 1964. That had been a once-in-a-lifetime luxury redolent of that particular period of rapid growth and change in Japan.

Basket of matsutake; picture drawn by Noriko Morishita

For all Morishita’s humor, food also evokes the people she has lost and the changes she has seen. Eating カレーパン(rolls stuffed with curry) reminds her of the roughness of her father’s face when he hugged her. And although she had disliked ohagi (a ball of sweet rice covered with sweet azuki beans) as a child, her father always loved the ohagi his mother would make him. Now that both her father and grandmother are gone, Morishita is occasionally overcome with a hunger for ohagi that is clearly akin to her longing for her family.

Half-eaten ohagi; picture drawn by Noriko Morishita

In her final essay, Morishita writes of finally beginning to learn to cook herself once she realizes that her mother is too old to cook anymore. Fittingly, she uses the memories of all the food she’s eaten to recreate dishes.

In the Afterword, Morishita describes the effect that food has on her:

The very instant I begin to eat something, I’m overcome by a strange sensation. The taste and smell of that food triggers the joy and painful longing that I experienced at some point in the past…. When we put food into our mouths, we are also consuming our mood and impressions at that time, in that place. They enter our mouths together with our food and build up somewhere deep within us until one day, when we encounter the same or similar tastes, we are brought back to a vivid memory, just as when you pull out your bookmark and open the pages of a book.

In her essays, Morishita succeeds in passing her food memories on to the reader. Somehow, she made me nostalgic for foods I have never eaten, and places in which I have never lived. She evoked the spirit of optimism in Japan during the 1950s to 1980s, but also the sheer enthusiasm of a child presented with new tastes and experiences. Although Morishita has had disappointments in her life, her essays suggest that food and its associations will always be a lifeline for her.