Empire R

R帝国、中村文則、中央公論新社、2017

Empire R, Fuminori Nakamura’s most recent book, starts with a quote from Adolf Hitler: “The great masses of the people will more easily fall victim to a big lie than a small one.” Nakamura starts as he means to go on—he doesn’t pull any punches in this novel, nor does he let the reader get comfortable. There are shades here of Aldoux Huxley, George Orwell, Czeslaw Milosz and Milan Kundera, as well as stories that could have been taken from our morning newspaper. On one level, this novel can be read simply as a thriller, but I think most of us will be unable to get through this novel with our complacency intact.

As the novel starts, Yazaki wakes up and learns that his country, Empire R, has bombed Country B in “self-defense” after discovering that the country was preparing to launch nuclear weapons. In an echo of Orwell’s 1984 (“Winston could not definitely remember a time when his country has not been at war”), Yazaki has a vague sense that there was a war just two months ago. This is a world in which everyone carries HP (human phone), artificial intelligence terminals that give the user all the information they need. They talk in human voices, and gradually acquire personalities based on their owner’s personality and their Internet search propensities. They can start conversations on their own, and even interact with other HP online. AI has already reached the point at which it can learn independently and program itself, so that it can surpass human intelligence.

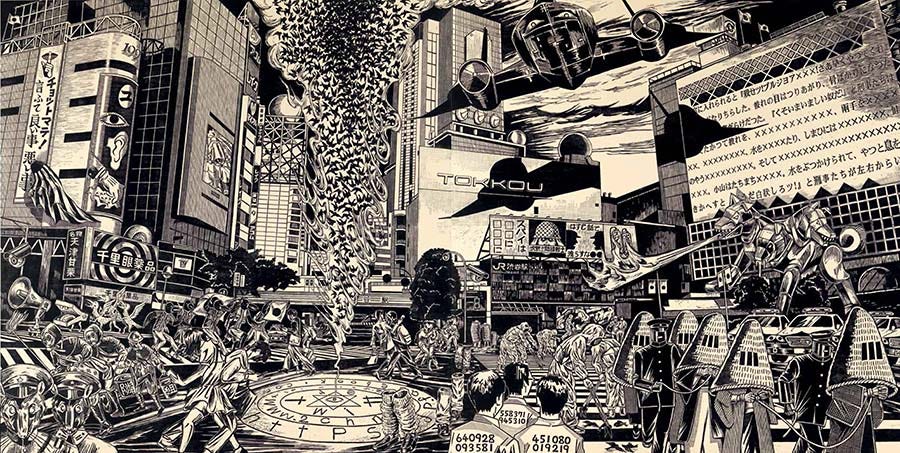

Shinjuku, by Carl Randall

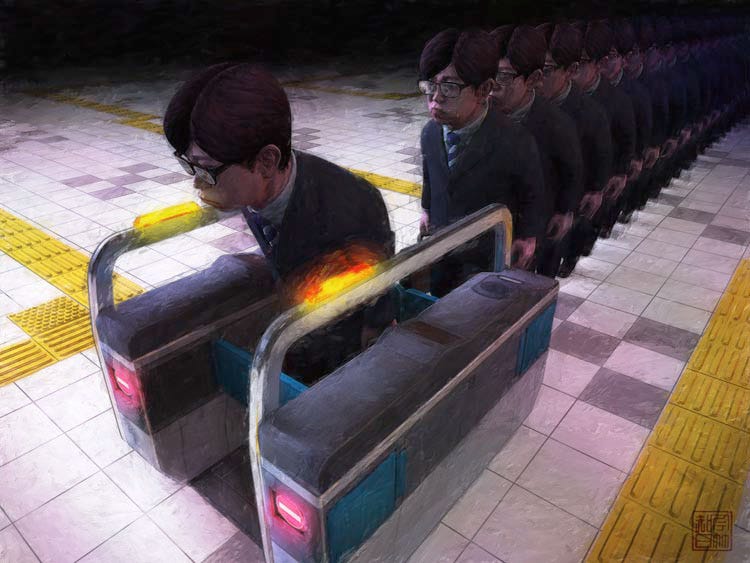

When the government suspends Internet access due to the war, Yazaki notices that his fellow train passengers panic—even their breathing becomes erratic—because HP have become such an extension of their bodies that they cannot imagine doing without them (luckily, they remember that they can still play games on their HP). In a telling detail, railings have been installed on the train station platform to keep people walking safely in single file so that they can keep their eyes glued to their HP.

Automatic Ticket Gate, by Satoru Imatake

This is the country that squadrons of soldiers from Republic Y land attack, chanting “God is everything, death to the infidels.” Yazaki’s HP guides him to relative safety in a library basement, but his usual blind acceptance of his surroundings crumbles as he is forced to question the motives of his fellow escapees. His trusting nature is shaken even more when he is rescued by Alpha, a female soldier from Republic Y, and learns her story.

Yazaki’s adventures are interspersed with the story of Kurihara, the secretary to a politician in the opposition party. They have no influence, but the ruling party insists that Empire R is a democracy, and this façade cannot be maintained without an opposition party. After the horrors of the street fighting (this book requires a strong stomach), it is a relief when Nakamura turns to Kurihara’s story and what seems—at first—to be a less bloody battle. It is a relief to find that he is an essentially good person—he cannot stand the live feed of an execution playing in the taxi and has to jump out and throw up on the side of the road, and he refuses to rely on his HP.

In fact, for all of the dystopian elements of this novel, Nakamura’s two main characters, Yazaki and Kurihara, seem to fit the mold of traditonal heroes. They have their weaknesses and flaws (Yazaki more overtly so than Kurihara), but they are consistently brave and willing to make sacrifices. The two ancillary female characters, Alpha and Saki, also share these characteristics. Empire R also has many of the tropes you would find in thriller novels: double agents, targeted viruses, underground resistance groups, kidnappings, pills that erase your memory and betrayal.

However, unlike the usual thriller, I wasn’t able to dismiss the story when I set it down. The details that Nakamura casually drops show up resemblances between this dystopian world and our own, effectively skewering our self-regard. The oceans are crowded with small boats full of immigrants, and if they are lucky they will be rescued by large companies in exchange for their labor. There are now 800 nuclear plants in Empire R, with the fourth nuclear accident occurring just after Yazaki was born. Commercials and ads are everywhere, but all are focused on children as part of the government’s push to raise the birth rate. 1% of the population is ultra-wealthy, 15% are wealthy, and 84% are poor. Wars are fought over oil and also to sustain the munitions industry, which is equivalent to a public utility now.

Sachiko Kazama, Nonhuman crossing 2013

Nakamura also shakes up the reader by identifying countries only by a single letter, which effectively strips them of the history and identity often embedded in a country’s name. Countries G and Y, both following the Yoma religion but different sects, are later consolidated and become Country GY. Even the shadowy resistance group is known simply as “L,” which seems to rob it of uniqueness and also any hope of succeeding.

Some 10 years earlier, novels with titles like “Auschwitz,” “9/11” and “The Rwanda Genocide” had appeared on the Internet. No one knew where they had come from or who had written them, but people theorized that an Internet bug was responsible, or that perhaps they had been created by artificial intelligence. Similarly, there were rumors that the revolutionary group L had tried to overthrow Empire R and establish a dictatorship. Even if one wanted to learn the truth of it, all of the original news articles had been erased from the Internet and replaced with massive amounts of conflicting information so that it was no longer possible to find the “truth.”

In Milan Kundera’s “The Book of Laughter and Forgetting,” Hubl, a historian about to be sent to prison, says, “The first step in liquidating a people … is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have somebody write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long the nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was. The world around it will forget even faster.” Kundera went into exile, but the characters in Empire R do not have that option—the entire world seems to have gone in the same direction, but few seem to notice or care.

Kaga, the shadowy figure behind the Party, insists that people don’t want the truth, they want the kind of happiness that can be found on a screen. He believes that people are tired—tired of having to be intellectual, independent, charitable, cooperative. The scariest part of this book—far more than the horrific war scenes—is the possibility that Kaga might be right, and that Saki and her fellow dissidents’ efforts to reveal the “truth” will not penetrate the minds of people addicted to immediate gratification. Things have not changed much since 1949, when Orwell published 1984 and wrote, “The choice for mankind lay between freedom and happiness, and…for the great bulk of mankind, happiness was better.”